This tutorial outlines the basics needed for working with the UNIX shell environment. These are UNIX commands and thus they apply to Linux and Mac operating systems. Windows machines cannot run UNIX commands locally and will require additional software to do so (see below).

Learning outcomes

- Interpret and implement absolute and relative paths in a UNIX hierarchy

- Recognise the various UNIX commands for navigation, creation, manipulation and viewing folders and files in UNIX

Prerequisities

An understanding of computer programming basics such as variables. These are covered in the Concepts in computer programming tutorial.

Useful (Extra) Material

A UNIX cheat sheet like this one might be helpful as a reference.

For more info on using the unix shell check out Software Carpentry tutorial.

Sandbox.io has a web-based UNIX shell for practise along with a wealth of tutorials to follow

Accessing the command line/terminal

Windows Users

Windows computers do not natively run UNIX. In order to follow the tutorial, please install Git for Windows, a software system that emulates UNIX. Accept the default install settings. To access the program, search for ‘Git for Windows’ in your Windows Explorer. The Git for Windows folder should contain a program called ‘Git Bash.’ Double-click this to execute. You can now follow the rest of the tutorial.

OSX Users

Apple computers natively run UNIX (except for a few commands like wget). To do the tutorial on your own computer, you can go to Applications -> Utilities -> Terminal and double click. This will bring up a command line for you to use for the tutorial.

Linux Users

Linux computers are built upon UNIX and so you can run this tutorial locally if you wish. The easiest way to find the terminal is to search for ‘terminal’ in the search bar. The terminal is where you can then input the commands for the tutorial.

Web-based practice environment

If none fo the above work for you, you can use the Sandbox.io web-based environment to practise.

Tip for practicing UNIX

UNIX can create and remove and overwrite files in a way you are not used to at the start. For practising, I usually recommend creating a new profile on your laptop (practiseProfile or something) and using that to practise UNIX, so you dont erase files you need by mistake!

Directory structure

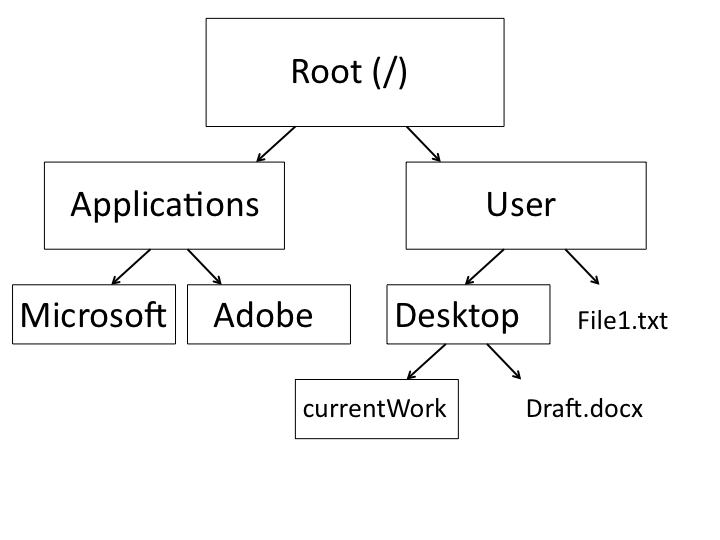

A computer file system is laid out as a hierarchical multifurcating tree structure. This may sound confusing but it is easy to think of it as boxes of boxes where each box is a directory.

There is one big box called the root. All other boxes are contained in this one big box. Boxes have labels such as ‘Users’ or ‘Applications’. Each box may contain more boxes (like Desktop or Downloads or Work) or files (like ‘file1.txt’ or ‘draft.docx’).

Thus it is hierarchical (boxes in boxes), multifurcating (each box can contain multiple boxes or files) tree structure (similar to how a tree has branches and leaves).

There are two ways to refer to directories and their positions in this hierarchy and relationship to other directories:

Absolute path

The absolute path is the list of all directories starting from the root that lead to the current directory.

Directories are separated using a /

For example, the path to the directory ‘Microsoft’ is /Applications/Microsoft/

What is the absolute path to the directory ‘currentWork’?

Relative path

A directory can also be referred to by its relative location from some other directory (usually where you are working from).

The parent of a directory is referred to using ..

- For example, if I am in ‘currentWork’ and want to get to ‘Microsoft’ the relative path is ../../../Applications/Microsoft/

What is the relative path from ‘Adobe’ to ‘Desktop’?

Important obscure keys

There are some keys that are used a lot in UNIX commands but can be difficult to find on many keyboards. Try to find now the following keys:\

- ~ (tilde)

- / (forward slash)

- \ (back slash)

- | (vertical bar or pipe)

- # (hash or number or gate sign)

- $ (dollar sign)

- * (asterisk)

Basic Syntax

Unix commands follow the general format of:

command -options target

The command comes first (such as cd or ls as we will see later) then any options (always proceeded by a – and also called flags) and then the target (such as the file to move or the directory to list).

These commands are written on the prompt (terminal command line).

Not all commands need options (sometimes called flags, and generally preceded by a single or double hyphen (- or --)) or targets, but others require them.

Note: all commands, options and targets are case sensitive.

- For example:

cd Desktopuses the commandcd(change directory) and the targetDesktopto move from the current directory into the subdirectory called “Desktop”ls -l Desktopuses the commandls(list), the option-lfor long-list, and the targetDesktopto list the contents of Desktop in the “long list” format, which provides more thorough descriptions than does the regular “ls”.

Notes on syntax for directory structure

- Two dots (

..) indicates the parent directory of the present working directory. So, for example,cd ..will move you back one directory. - One dot (

.) indicates the present working directory. So, for example,cd .will keep you where you are. There are times where the single dot can be more useful than this… - The tilde (

~) refers to your home directory (your user profile in your laptop). If you want to refer to something in that directory(e.g. the Desktop in the image example above) you can use ~/Desktop as the path. - A forward slash (

/) by itself or at the start of a path refers to the root of the filing system – the folder that contains all other folders.

Some suggestions concerning file and folder names

- Avoid spaces in script and filenames (use underscores, dots, or hyphens, use “CamelBack” notation). You can see above that commands, options and targets are separated by spaces, so spaces in filenames confuse this.

- Do not use “weird” characters (#@!*&^, etc., especially ?, *, \, or /)

Don’t Panic

When it all goes south, control-c is your friend. It breaks whatever processes are running, and gives you your prompt back. Or, failing that, just close the Terminal and start again.

Helpful typing shortcuts

- Tab will auto complete text for you (see full description in the advanced tutorial).

- The up arrow will bring up commands you typed previously.

Print to the screen (Our first command)

Lets start with a very basic command: echo. Echo just prints to the screen whatever text we put after it. E.g.

echo "Hello World!"

will print Hello World!. Try it now.

Navigating

In order to navigate around the directory structure you first need to know where you are in that structure currently. This is done using the command

pwd

This will print your working directory (the directory you are currently in).

Next, type:

ls

This lists the contents of your working directory (which is likely empty).

You can also look at the contents of any other directory by supplying the path (absolute or relative). For instance:

ls ..

will list the contents of the parent directory that your current directory is in. You can use flags to modify this view. For example

ls -l

will give you a list view with each item on its own line.

ls -a

gives you all the files, including hidden ones such as those that point to the parent (..)

You can often combine flags such as

ls -la

which gives you all the files, including hidden ones, in a list format.

Getting around the directory hierarchy is done using the cd command (change directory). The syntax is:

cd <absolute or relative path>

For example, in the example hierarchy above, to go to the Microsoft folder we would use

cd /Applications/Microsoft/

or if we were currently in the ‘currentWork’ folder we would use

cd ../../../Applications/Microsoft/

We can move into the parent of the folder you are currently in by typing

cd ..

If you type ls you can see your home directory is listed here.

You can use pwd to confirm you’ve moved and are now in a new working directory.

You can move back to your home directory by typing cd with no arguments.

This is a handy trick if you are lost in the filesystem and want to get home!

cd

Try using the up arrow to browse through the commands that you just used.

Creating directories and files

mkdir is the command to make a directory. Type

mkdir myfolder

to make a new folder called myfolder. Type ls and then enter. You should now see ‘myfolder’ in the list.

Creating files can be done in many ways. The most common method is to use a command line text editor. Here we will use nano but there are many others (emacs, vi etc) that are more powerful.

NOTE: if nano is not installed on your computer, but you have conda installed, you can install nano via conda as outlined in the Conda tutorial.

Create a file called file1.txt in the unix folder by typing

nano file1.txt

This will launch the nano text editor and allow you to edit file1.txt. If file1.txt doesn’t exist, it will create it for you; if it does exist, it will edit the document.

Write in here ‘this is the contents of file1.txt’.

Save the file by pressing ctrl-o (press control and then press o). This will prompt you at the bottom of the screen to confirm the file name and you can press return/enter to confirm this.

Exit nano by pressing ctrl-x (and hitting return/enter). This will return you to your prompt.

If you list the contents of your current directory (using ls) you should see file1.txt is now there.

If you don’t have nano or conda to install it, you can create this file with this content by using the echo and redirect commands like this:

echo ‘this is the contents of file1.txt’ >file1.txt

Copying, renaming, and moving files

The copy command (cp) is used to copy files to new places. This command has 2 targets: the file you want to copy and where you want to copy it to. The command basic syntax is

cp source_file destination_file

We will now make a copy of file1.txt called file2.txt by typing:

cp file1.txt file2.txt

We can also cp a file from the shared directory using absolute and relative paths.

cp /class/shared/testfile.txt .

The period (.) at the end of the command is important. This states that the target location is the current directory (we told you it had some uses!).

This command will copy a file named “testfile.txt” to your current directory but will not change its name. Use ls to verify.

The move command (mv) can be used to both move or rename files. The command syntax is

mv source destination

If you give a filename as the destination, the file will be moved to this new filename. If you give a folder name as the destination, this file will be moved to that folder, but keep the same name.

For example

mv testfile.txt example.txt

has the effect of renaming testfile.txt to example.txt.

mv example.txt myfolder

has the effect of moving example.txt to the subdirectory myfolder but keeping the same filename.

- NOTE: Do not move files that are not in your home directory or a subdirectory of this. All files in shared or root folders are to be copied, never moved.

Viewing file contents

You can use a text editor like nano to view the contents of text files but this can be tedious and difficult for very large files.

There are several commands for viewing files without an editor, depending on how you wish to view them.

To print the entire contents of a file to screen you can use the command

cat filename

This will display all the contents at once. This is ok for small files (a few lines) but larger files will run on and on.

For large files it is better to use interactive viewers. One such viewer is less, invoked by typing

less filename

the file is then displayed one screen length at a time.

Certain commands are then used to go back and forward through the file:

- space bar: display the next page

- b: display the previous page

- enter/return: display the next line

- k: display the previous line

- q: quit the viewer

If a file contains very long lines, these lines will wrap to fit the screen width. This can result in a confusing display, especially if there are, for example, long sequences in your file. To stop this we can use

less -S <filename>

which will stop the text wrapping. You can scroll horizontally across lines using the arrow keys.

To view a certain number of lines at the start or end of a file we use head and tail. For example, to view the file 50 lines of a file type

head -n 50 filename

Here we see the flag/option -n is used to denote the number of lines we want followed by the number itself. The same can be done using tail to view the last lines of a file.

Tasks to practice

Navigating and creating

- Navigate to your home directory

- Create a fodler called UNIXtest

- Navigate into that folder

- Create an empty file called testFile1.txt

Renaming and moving

- Create an empty file called testFile1.txt

- Copy the file to testFile2.txt

- Rename testFile2.txt to testFile3.txt, keeping it within the same folder

- Move testFile3.txt to the parent directory and rename it testFile4.txt

Advanced UNIX tutorial (shell scripting)

If you wish to learn more about the expansive uses and advanced commands in UNIX, you can go to the UNIX tutorial advanced.

Setting up conda

For installing programs in a UNIX environment, conda is suggested as the package management system. Follow the Conda tutorial for details on how to do this.